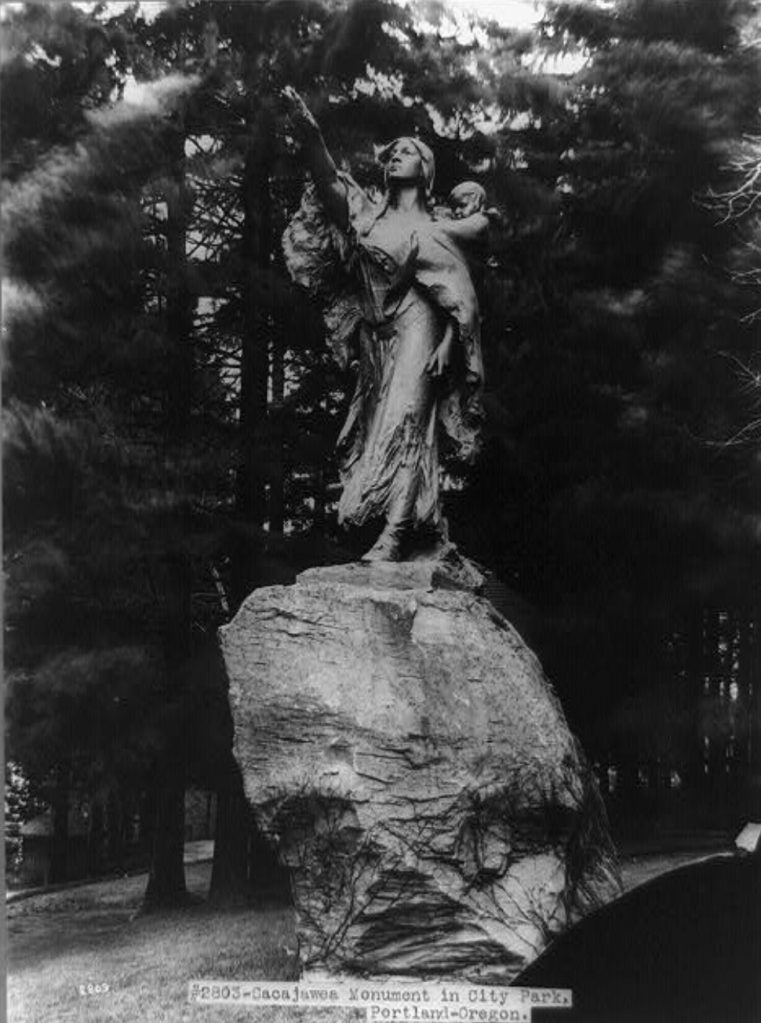

Alice Cooper, or Alice Cooper Hubbard, was a midwestern sculptor who studied with Lorado Taft. Her best known work is probably the over-lifesize 1912 monument to Shoshone explorer and guide Sacajawea, who famously guided the Lewis and Clark expedition to the Pacific Ocean, having given birth to her son Jean-Baptiste along the way. Cooper depicted Sacajawea pointing confidently west, in the direction of the ocean, with her infant son carried in a sling on her back. An embodiment of the perfection of late American neoclassical sculpture, this dramatic monument was undertaken at a time when women had still not won the right to vote: the suffrage fight was ongoing.

From Oregon visual arts: “Sacajawea and Jean-Baptiste” was commissioned by the Committee of Portland Women as the centerpiece for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition to represent “the only woman in the Lewis and Clark Expedition and in honor of the pioneer mother of old Oregon.” It originally stood in the center of the Plaza at the Lewis and Clark Fair in 1905, at the end of which, it was moved to Washington Park. Sacajawea was a Shoshone woman who guided Lewis and Clark in their journey westward. At the time this sculpture was commissioned, equal suffrage was not yet in effect and the women of Oregon were still fighting for the right to vote. Many prominent women suffragists were present at its dedication including, Susan B. Anthony, Rev. Anna Shaw and Mrs. Abigail Scott Duniway. Funds for the work were raised by women across the western states. Alice Cooper of Denver was selected to design the work. She is the first woman artist to be represented in Portland’s Public Art Collection.

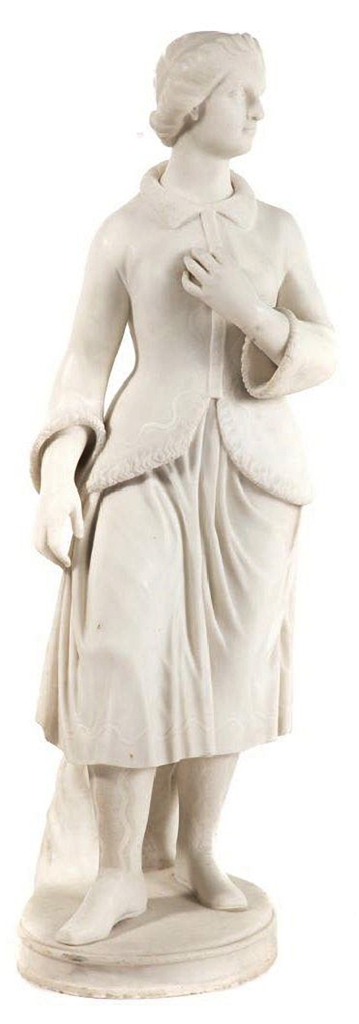

Sculptor Lorado Taft, who taught at the University of Chicago, hired his most talented students to construct the enormous number of plaster sculptures needed for the magical “White City” at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Known as the “White Rabbits”–perhaps because they were perpetually covered in a fine sift of plaster dust–the group of students included Bessie Potter Vonnoh and Helen Farnsworth Mears. Mears, who was commissioned to sculpt Genius of Wisconsin for the fair, went on to study with Augustus Saint-Gaudens and complete various public commissions, including a statue of the suffragist Frances E. Willard for the U.S. Capitol. When Taft, who was overseeing the fair’s sculptural ornament, asked chief architect Daniel Burnham if he could hire women, Burnham reportedly replied, “Hire anyone, even white rabbits if they’ll work!”

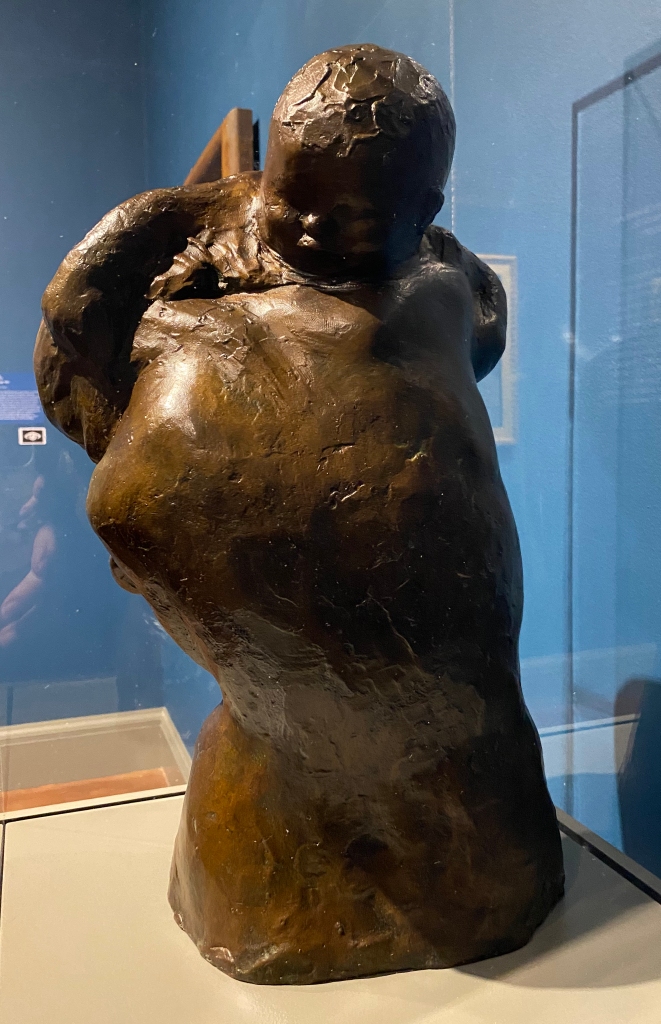

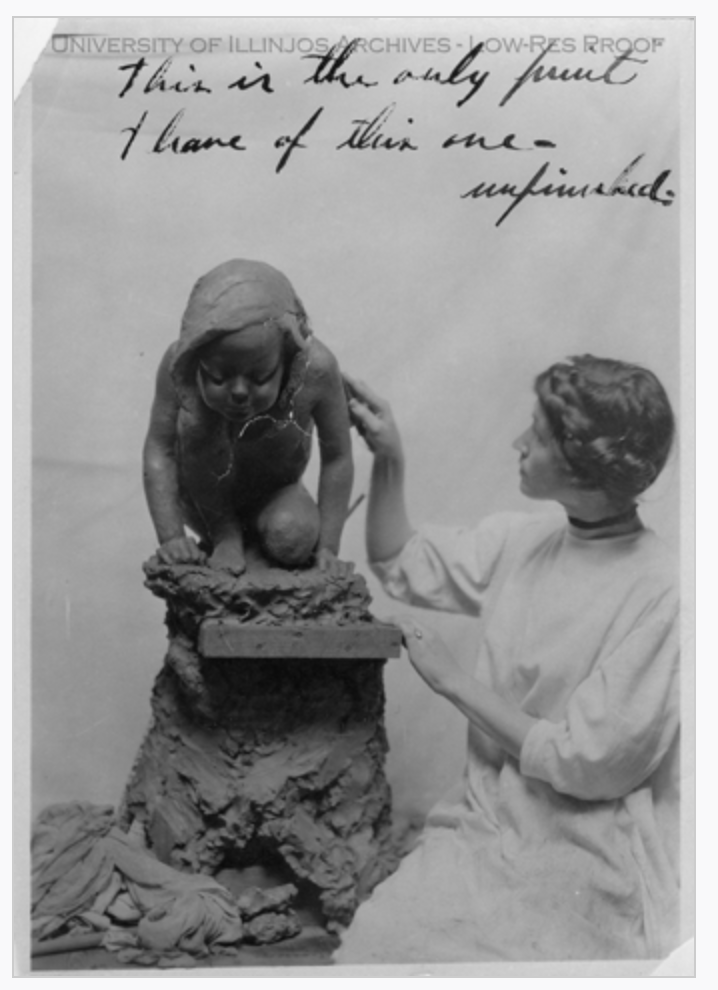

Not enough is known about Alice Cooper, who must have been one of the Chicago World’s Fair sculptors. These young women are regrettably not identified individually in contemporary photographs of them at work on monumental White City sculptures. A picture of Alice as a very young woman, working on a lifesize sculpture of a small child, is in the University of Illinois archives. This is described as: “Photo of sculptor Alice Cooper Hubbard of Des Moines, Iowa, and a work in progress. Script on front of photo reads This is the only print I have of this one – unfinished.”

Images: Alice Cooper, Sacajawea and Jean-Baptiste. Bronze, 1905. 7 x 3 1/2 x 3 feet.

More about the White Rabbits: https://interactive.wttw.com/art-design-chicago/white-rabbits