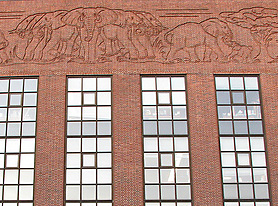

Elephant frieze on Harvard's Biology Lab building

Katherine Ward Lane Weems (1899 – 1989) was the daughter of the president of the board of trustees of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Among her mentors were John Singer Sargent and Anna Hyatt Huntington, who both had studios nearby. Anna Hyatt became an inspiration and introduced her to leading figures at the National Sculpture Society. In 1926, Lane won a Bronze Medal at the Philadelphia Sesquicentennial Exposition, and the Widener Medal at the Pennsylvania Academy.

In 1933 she was given the commission to create a frieze of elephants on the red brick facade of the Harvard University Biology lab. This was accomplished by chiseling the exterior of the building with a pneumatic drill, creating a linear frieze with over 30 animals across the building’s top story, installing three bronze doors, and creating a pair of larger-than-life bronze rhinos for the front steps. Her other commissioned monuments still on view in Boston are the six dolphins at the New England Aquarium and the fountain at the Boston Esplanade Plaza.

Lane married in 1947 but continued to exhibit under her maiden name. She was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and became a full academician of the National Academy. In 1965 a permanent gallery was established at the Boston Museum of Science to show her small animal bronzes and drawings, and in 1987 the museum established the Katherine Lane Weems Chair in Decorative Arts.

Far from unknown, Anna Hyatt Huntington’s truly stupendous body of work has nonetheless been consigned to the back shelf (if not exactly the dustbin) of history.

Far from unknown, Anna Hyatt Huntington’s truly stupendous body of work has nonetheless been consigned to the back shelf (if not exactly the dustbin) of history. I am often asked what “bonded bronze” and “bonded marble” (or, for that matter, “cold cast” marble, bronze, etc.) are. Be aware that they are not real bronze, or stone. I consider these to be a faux finish on plastic resin, since they are made by mixing bronze or marble powder with the first (and very thin) layer of resin when casting polyurethane or other resins in a mold. They are not weatherproof, since polyurethane resin degrades when exposed to UV radiation or even seasonal (think: midwestern) temperature fluctuations. Nor are they very sturdy (treated carefully, most of my plaster pieces have actually held up better over time).

I am often asked what “bonded bronze” and “bonded marble” (or, for that matter, “cold cast” marble, bronze, etc.) are. Be aware that they are not real bronze, or stone. I consider these to be a faux finish on plastic resin, since they are made by mixing bronze or marble powder with the first (and very thin) layer of resin when casting polyurethane or other resins in a mold. They are not weatherproof, since polyurethane resin degrades when exposed to UV radiation or even seasonal (think: midwestern) temperature fluctuations. Nor are they very sturdy (treated carefully, most of my plaster pieces have actually held up better over time). Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872-1955) was a St. Louis native who studied in Chicago with sculptor Lorado Taft from the age of 15. She later assisted Taft in works he created for the World’s Columbian Exposition and received a separate commission for an eight-foot figure, “Art”, for the Illinois State Building at the fair. At the age of 22, she opened her own studio in Chicago.

Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872-1955) was a St. Louis native who studied in Chicago with sculptor Lorado Taft from the age of 15. She later assisted Taft in works he created for the World’s Columbian Exposition and received a separate commission for an eight-foot figure, “Art”, for the Illinois State Building at the fair. At the age of 22, she opened her own studio in Chicago. When you’re searching the hardware store for materials, you’ve probably wondered: What’s the difference between all these plaster varieties, anyway? Here are my empirical observations:

When you’re searching the hardware store for materials, you’ve probably wondered: What’s the difference between all these plaster varieties, anyway? Here are my empirical observations: Anne Whitney (1821-1915) ran a girl’s boarding school in Salem, Massachusetts. She sculpted many notable figures in Massachusetts history, among them a full-length Samuel Adams for the National Statuary Hall complex in Washington, DC.

Anne Whitney (1821-1915) ran a girl’s boarding school in Salem, Massachusetts. She sculpted many notable figures in Massachusetts history, among them a full-length Samuel Adams for the National Statuary Hall complex in Washington, DC. Vinnie Ream was the first woman and the youngest artist to ever receive a commission from the United States Government for a statue.

Vinnie Ream was the first woman and the youngest artist to ever receive a commission from the United States Government for a statue. Harriet Hosmer was born in Watertown, Mass. in 1830. Denied entrance to medical colleges on the East Coast, she visited friends in St. Louis and took anatomy classes at Missouri Medical College. Hosmer then traveled to Rome, where she studied sculpture and soon set up a studio of her own. Her work, mainly executed in marble, became very popular with European royalty and American visitors to Rome like Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hosmer’s twice-lifesize bronze monument of Thomas Hart Benton (left) was unveiled in St. Louis in 1868. At the peak of her career, Hosmer employed more than 20 (male) artisans in her Rome studio, and had to defend her reputation from claims that these artisans were the real creators of her work.

Harriet Hosmer was born in Watertown, Mass. in 1830. Denied entrance to medical colleges on the East Coast, she visited friends in St. Louis and took anatomy classes at Missouri Medical College. Hosmer then traveled to Rome, where she studied sculpture and soon set up a studio of her own. Her work, mainly executed in marble, became very popular with European royalty and American visitors to Rome like Nathaniel Hawthorne. Hosmer’s twice-lifesize bronze monument of Thomas Hart Benton (left) was unveiled in St. Louis in 1868. At the peak of her career, Hosmer employed more than 20 (male) artisans in her Rome studio, and had to defend her reputation from claims that these artisans were the real creators of her work. Molds: The big secret of the sculpture trade

Molds: The big secret of the sculpture trade Emma Stebbins is the sculptor of “The Angel of the Waters” (1873), also known as “Bethesda Fountain,” located on the Bethesda Terrace in Central Park, New York. According to Central Park historian Sara Cedar Miller, Stebbins received the commission for the sculpture as a result of influence from her brother Henry, who at the time was president of the Central Park Board of Commissioners. Henry was proud of his sister’s talent and hoped to have many examples of her art in Central Park.

Emma Stebbins is the sculptor of “The Angel of the Waters” (1873), also known as “Bethesda Fountain,” located on the Bethesda Terrace in Central Park, New York. According to Central Park historian Sara Cedar Miller, Stebbins received the commission for the sculpture as a result of influence from her brother Henry, who at the time was president of the Central Park Board of Commissioners. Henry was proud of his sister’s talent and hoped to have many examples of her art in Central Park.