When I think of the large number of women sculptors in America in the 19th and early 20th century, I find them an empowering delight and also an enigma. In a time when women’s aspirations generally were limited to home and family, these women sculptors seem to me a kind of seismic anomaly. The boldness of their accomplishments is pushed into high relief (pardon the bad pun) on the dull plain of female possibility, not least because many of them received recognition in the form of patronage and publicity little different from their male peers.

Some of these women never married, and others (Harriet Hosmer and Emma Stebbins, for example) were gay. Hosmer and Stebbins lived in an expatriate micro-society of their own creation in Rome, and were never subject to the toil of traditional marriage and family life.

Of those who married, we know that Vinnie Ream Hoxie was forbidden by her husband to work after her marriage. He relented when Vinnie became ill with the kidney disease that eventually caused her death, and constructed a harness-like seat so Vinnie could be winched up to the top to of her final, large-scale piece. Evelyn Longman Batchelder, on the other hand, was encouraged by her husband to pursue a career and set up a studio after their marriage.

Other sculptors, like Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and Anna Hyatt Huntington had the (vast) personal means to maintain several studios and hire as much help as was needed to complete their monument-sized work. Anna Hyatt Huntington in particular had a spacious studio complex and surrounded herself with what seems like a small army of models, students, and assistants. Others came from families of modest means and earned their own living. Evelyn Longman worked in a dry goods store by day to pay for her evening sculpture classes at the Chicago Art Institute. Farmgirl Vinnie Ream (often described as unscrupulously using her feminine “wiles”) enlisted the aid of President Lincoln precisely because she was a poor girl making her own way in the world.

In the years after the Civil War, when the United States was becoming a world power, public acknowledgement of national triumphs and tragedies seemed to require larger-than-life memorialization. Both male and female sculptors employed large studios to satisfy demand for war memorials, equestrian monuments, and funerary sculpture, as well as portrait busts for the wealthy and well-known.

But the question I keep coming back to is: why, comparatively, were there so many women, and why were they well accepted in a male-dominated field? In an age when women were denied entrance to most professional schools, many young women sculptors were accepted and nurtured by successful male sculptors and learned their trade in the commercial studios of men like Lorado Taft, Henry Hudson Kitson, Hermon Atkins MacNeil, Daniel Chester French, and August Rodin. Was it that women sculptors offered such a remarkable exception to normal roles that they fell completely outside the pale and so became oddly exempt from society’s repressive expectations?

Unlike the handwork of unknown 19th-century women, sculpture exists in sturdy bronze and marble and–while occasionally displaced or damaged like Edmonia Lewis’s masterpiece, “Death of Cleopatra”–stands literally in your face, in the town square, or even in Central Park. Misattribution occurs (no one I spoke to at Bethesda Fountain ever knew that “Angel of the Waters” was by a woman), but the work itself can’t be denied.

Abastenia St. Leger Eberle (1878–1942) was a native of Webster City, Iowa. She initially studied to become a professional musician, but eventually enrolled in the Art Students League in New York.

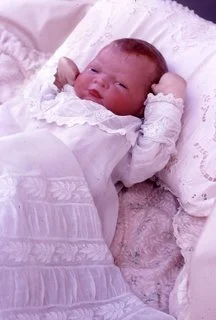

Abastenia St. Leger Eberle (1878–1942) was a native of Webster City, Iowa. She initially studied to become a professional musician, but eventually enrolled in the Art Students League in New York. Sculptor Grace Storey Putnam is one of the most well-known doll designers of all time.

Sculptor Grace Storey Putnam is one of the most well-known doll designers of all time. Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson (1871 – 1932), also known as Tho. A. R. Kitson, was an American sculptor born in Brookline, Massachusetts. As a young child she displayed artistic talent, but when her mother attempted to enroll her in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, she was informed that the program did not accept female students.

Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson (1871 – 1932), also known as Tho. A. R. Kitson, was an American sculptor born in Brookline, Massachusetts. As a young child she displayed artistic talent, but when her mother attempted to enroll her in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, she was informed that the program did not accept female students.