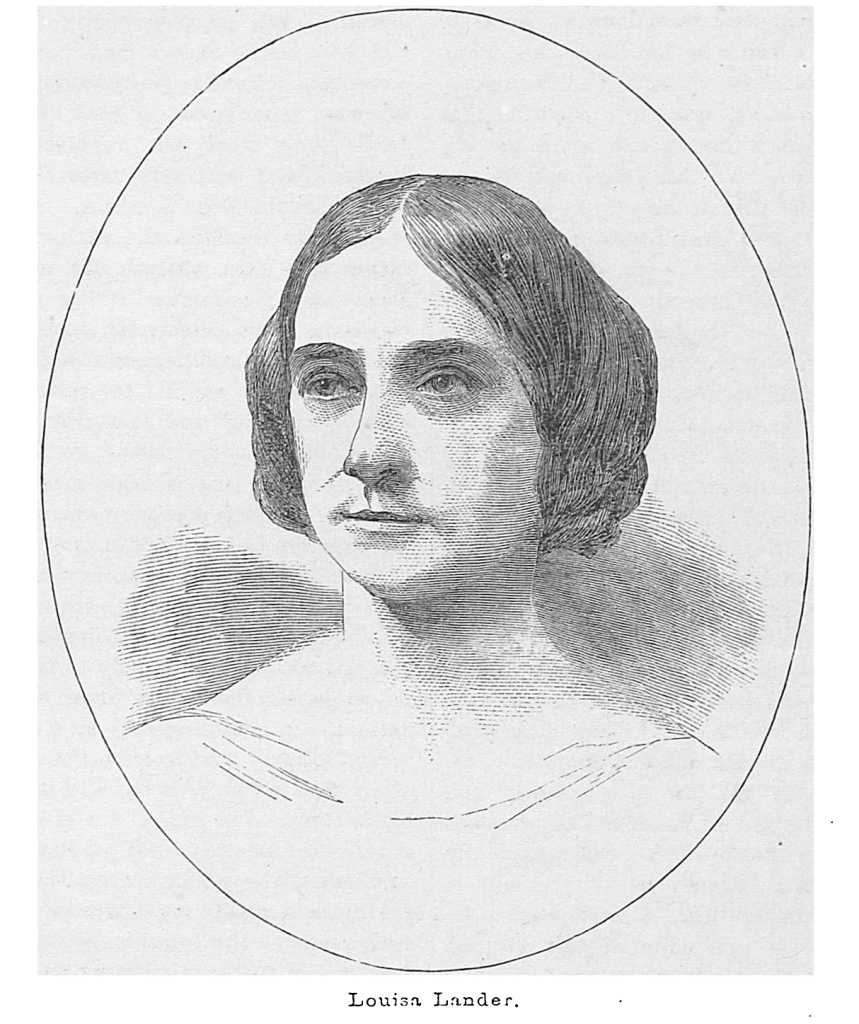

This is the second of a two-part article which re-frames the career of sculptor Louisa Lander, documenting her dates and places of residence an making new attributions to her oeuvre. See notes and sources at the end of this section, and images in the next post.

Harriet Hosmer: Another Roman Scandal

The sculptor Harriet Hosmer, who grew up near Boston, arrived in Rome in 1852 and became a pupil of British Sculptor John Gibson. Her studio was near Lander’s, in a large building that had belonged to Antonio Canova and had been divided into several smaller spaces. Hosmer’s wide and influential social circle included renowned actress Charlotte Cushman, sculptor Emma Stebbins, African American sculptor Edmonia Lewis, and other American expatriate sculptors including William Wetmore Story. Hosmer cultivated friends and patrons in the British aristocracy, and local celebrities like the Barret Brownings, who lived in Florence. An excellent horsewoman who was fond of games and wrote humorous poetry, Hosmer was popular and outgoing, in contrast to the retiring, quiet Lander. When her own scandal broke in 1863, Hosmer, no doubt the wiser for seeing how Lander had been treated, was prepared to wage battle and rallied her many friends.

Hosmer’s masterwork, Zenobia in Chains, represented the captured queen of Palmyra as she was paraded in defeat through the streets of Rome. It received wide critical acclaim and was copied in several sizes, finding ready purchasers. However, a persistent rumor arose that Hosmer had not made the sculpture herself. This gossip was eventually published in British journals, notably an 1863 issue of The Queen. In an 1864 letter to the Art Journal, Hosmer pulled no punches, stating: “A woman artist who has been honored by frequent commissions is an object of peculiar odium. I am not particularly popular with any of my bretheren; but I may yet feel myself called upon to make public the name of one in whom these reports first originated…” Hosmer forced The Queen and Art Journal to print retractions; although she never publicly revealed the name of her detractor, she did so privately. 27

In a letter to her friend, sculptor Hiram Powers, Hosmer claimed that the American sculptor Joseph Mozier was the one who had slandered her work on “Zenobia.” None other than Thomas Crawford once said that Mozier had “completely burned out his heart with envy, jealousy and such charming passions.” 28 To vindicate herself once and for all, Hosmer wrote a description of a sculptor’s studio practice for The Atlantic Monthly that was complete and to the point. She outlined the staff of artisans who produced a large sculpture—from those who made the metal armature to those who made the mold and pointed up (enlarged or reduced), and others who chiseled marble drapery, human form, flowers, etc. depending on their area of specialization. Both male and female sculptors availed themselves of the marble artisans of Italy; in fact, it was one of the chief reasons that Greenough, Crawford, Story, Powers, and so many others established studios there.

Hosmer wrote a satiric poem, The Ballad of the Caffe Greco, in which the muse of tragedy, Melpomene, observes male artists gossip about female artists in Rome:

…Tis time my friends, we cogitate,

And make some desperate stand

Or else our sister artists here

Will drive us from the land.

It does seem hard that we at last

Have rivals in the clay

When for so many happy years

We had it all our way. 29

Perhaps it was Mozier, jealous and wishing to eliminate talented rivals, who initiated malicious gossip about Louisa Lander. Certainly Hosmer, referring to a successful woman as “an object of peculiar odium” was describing prejudice so widespread that it seems to apply to all women sculptors.

Lander Returns to the Boston Area in 1860

When Lander returned to America for good in 1860, she immediately began to show and sell pieces she shipped to Boston from Rome. Lander received press coverage and exhibits in the most prominent Boston venues, among them the Boston Athenaeum and the Williams & Everett Gallery. She also shipped sculpture to the prestigious Dusseldorf Gallery in New York City. Work shown at these galleries included her Evangeline, from Longfellow’s poem, a small statuette of Virginia Dare, the water nymph Undine, and a six-foot group of three figures, Pioneer Mother Defending Her Daughters.

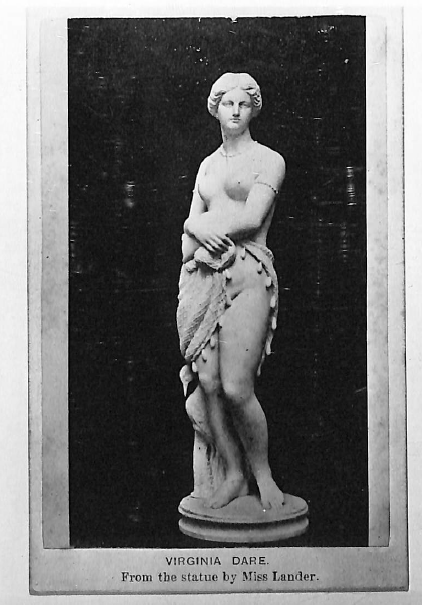

Virginia Dare

The story of Virginia Dare, the first white child born in America, was not widely known before Louisa Lander brought it to the nation’s attention during the Civil War. Lander evidently viewed an exhibit about the story of the lost colony of Roanoke at the British Museum, en route to Rome. That she imagined a common experience with Virginia Dare—a young girl growing up close to nature in the woods of America—must have been amplified by the freedom she experienced living in Rome. Her life size Virginia Dare sculpture was exhibited in downtown Boston’s Studio Building in 1861 for the benefit of Union troops (visitors were charged fifty cents), and Lander turned this publicity into a promotional opportunity. For the exhibit, Lander wrote a four-page pamphlet tellingly titled The National Statue. Lander’s two-page essay envisions a new American symbol—a young English woman living a life of Native American freedom in the southern wilderness. A list of Lander’s recent sculpture—most newly brought from Rome—is on the back of the pamphlet. A description of the history of the lost English colony at Roanoke indicates that the general public was unfamiliar with the Dare story. 30

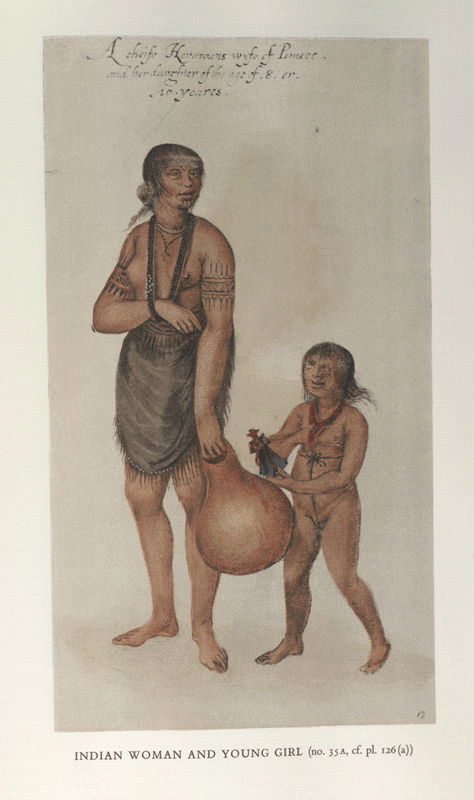

It’s not known exactly which images of the Roanoke colony Lander saw during her sojourn in the British Museum. It’s fascinating, however, to look at a drawing of a Native American woman—widely copied—by John White, the English expedition’s artist, and grandfather to baby Virginia Dare. With a couple of changes to the composition—placing a heron on the sculpture’s right, removing the pot carried by the woman in the drawing—the pose is strikingly similar, as is placement of the jewelry. Perhaps the heron at Virginia’s side is a clever nod to a different bird, the eagle accompanying America in the “Progress of Civilization.” There is a time-worn joke in the design business: “Good artists copy, great artists steal.” Whether Lander was good or great remains somewhat to be seen. But Louisa borrowed more than a simple pose: she chose to relay a frank and confident presentation of the self.

Lander was probably well aware that her intellectual contribution to American neoclassical sculpture was an ability to create new symbols from American lore and literature. Presenting a woman of self-possessed bearing as a “National Statue” runs counter to the fashionable, often semi-erotic, representation of women in neoclassical sculpture. For instance, the critically acclaimed Greek Slave, by Hiram Powers, to which Virginia Dare was sometimes compared, depicts a downcast, helpless young woman, nude and titillatingly chained to a post.

Louisa’s brother Frederick, the Union General, explorer, and writer, composed a descriptive poem about Virginia Dare, the statue (“She stands before us like a thing of dreams…” ), and took an opportunity to celebrate Louisa herself in the last verse.

…Ye arbiters of calling and true fame,

Translators of divinities ye blend

From faith and hope in Freedom’s household name;

Ye judges stern, whom sophistries offend,

Here view the grace that woman’s hand can lend

To all ye love; who, where eternal Rome

Bids artist souls to loftier themes ascend,

Could mould the tale of dear Virginia’s home,

And love her native land beneath a foreign dome. 31

Critics were still praising Virginia Dare in 1865, as in an essay signed by “W” in the March 16 Boston Evening Transcript:

VIRGINIA DARE

In this statue we see what we have long wished to see, our country represented by our sculptors. What have we to do with Palmyra, Europe and Africa? Let us congratulate Miss Lander on having nobly written the first page of our nation’s history in undying marble. “Zenobia” and “Africa” tell an old story, but in Virginia Dare centers an interest that stirs the heart of every true American….” 32

“W” notes that Lander did all the final finishing of the marble herself….preserving “the vitality that comes and only comes from the hand of genius.”

“W” ’s allusions to “Palmyra” and “Africa” are digs at two of Lander’s fellow American neoclassical sculptors, Harriet Hosmer (Zenobia in Chains) and Anne Whitney (Ethiopia Shall Soon Stretch Out Her Hands to God, also called “Africa”). W implicitly criticizes them for a lack of national pride in taking subjects from Greco-Roman mythology and ancient history. Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra, was captured by the Roman Emperor Aurelian; abolitionist Anne Whitney strove to represent a generic African “type” in her sculpture of a reclining nude African woman.

The Cosmopolitan Art Journal (Vol. 5) praises Lander: “The record shows not only the vast industry of the lady, but affords a pleasant proof of the progress made in Modern opinion as regards “woman’s sphere” and woman’s capabilities. That she is endowed with genius for her profession is conceded even by those hypocrites who cavail at “women-artists;” while, but the unbiased and discerning, she is regarded as one of those artists who will add lustre to the American name should her life be spared and she be permitted to pursue her profession uninterruptedly.” 33

In May of 1861, the Boston Evening Transcript reports that Louisa was “associated with Miss Dix” in assisting wounded soldiers in Washington, DC. Dorothea Dix had arrived in Washington, DC the month before to oversee army hospitals. No doubt Louisa was doing all she was able to support her brother, the Union Army, and the cause of her New England home. Louisa was back in Salem at 5 Summer Street in 1862, the year her father died and her champion, Frederick, succumbed to illness after the battle of Bloomery Gap and was buried at Broad Street in Salem. She and her sisters are recorded in the 1865 town census at that address.

Lander’s subject matter

Apart from her portraits, Louisa Lander’s subjects were women. Drawn from contemporary popular literature, myth, and folklore, they form a somewhat melancholy group. Only To-Day and Virginia Dare seem triumphant, each in charge of her own destiny. Most of Lander’s chosen subjects—the protagonists of her body of work—are women undergoing trial or transformation. Lander chose literary works with an eye to not only the popularity of the poem or story, but also the symbolic messages embodied by brave, betrayed, and independent female characters.

John Greenleaf Whittier, abolitionist poet, wrote the popular romantic poem Maud Muller in 1856. Published as an illustrated booklet, it tells the story of a young woman who, while working in her family’s hayfield, meets a handsome judge of higher social standing. The two exchange a few words and part, but each regrets the parting, and, in later life, both judge and girl (now a harried young mother) muse sadly on what might have been. Illustrations of the time portray Maud as a country girl with long, loose hair under a straw hat and a simple summer dress. This poem contains the well-known quotation: “For of all sad words of tongue or pen, The saddest are these: ‘It might have been!’” Lander’s bust of Maud is described as being under life size.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem Evangeline is the fictional saga of a young Acadian woman, separated from her lover during the British expulsions of Catholic Acadians from Canada. Evangeline searches faithfully for her beloved her whole life long and eventually is reunited with him as he lies on his deathbed. Lander’s Evangeline is an exhausted young girl, lying asleep by the bank of a stream surrounded by flowers.

Elizabeth, and the Exiles of Siberia, a romantic 1805 novel by Madame Sophie Cottin, tells the semi-factual story of a loyal young woman who follows her father into exile in the Siberian wilderness and is eventually instrumental in freeing him. Elizabeth is described as wearing a cap, short skirt, and “Russian” boots. The book’s descriptions of Elizabeth’s peasant costume are vivid: a short red petticoat, reindeer trousers, squirrel-skin boots, and fur bonnet.

Undine, a water nymph whose folktale has many variations, is a proto- Little Mermaid figure. Undine trades her immortality for mortal love, but will die if her human husband is unfaithful. The novelist and critic Baron Fouqué wrote a popularized version of this myth in 1811. Lander’s “Undine” is drooping as she arises from a fountain, surrounded by seashells which produce jets of spray. This piece most probably represents Undine as she is about to die, becoming, after her betrayal, a pool of water. 34

Elizabeth Ellet’s Roman source also mentions a “Ceres and Proserpine” and “Galatea” which illustrate well-known classical myths. In Lander’s work, a mourning Ceres waits for her daughter Proserpine to emerge from the underworld, where she is exiled for six months out of every year. Ellet describes Lander’s Ceres leaning sadly against a sheaf of wheat. Galatea, an idealized sculpture of a young woman, came to life because the goddess Venus rewarded the prayers of the (male) sculptor Pygmalion. No further description is given of the Galatea; there is a brief description of a “Sylph” gazing at a butterfly. 35 Perhaps these sculptures were never brought to the final carving stage and only existed as clay maquettes. Curiously, one of Louisa’s small cameos, an unfinished shell carving about two inches long, also depicts a young woman, possibly with wings, raising a hand on which a butterfly has alighted. A small cup from Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum is in the shape of a young woman’s head with long, flowing hair has handles in the shape of butterflies. 36

And then, there is the monumental, six-foot “Captive Pioneer Mother and Daughters,” which had many titles. It is—or was—a life-size group of three figures: a mother who stands in front of one cowering young daughter while another daughter lies at her feet in a faint. It was also referred to as “The White Mother Protecting Her Daughters from the Indians,” and “America Defending Her Children.” The June 25, 1861 Boston Evening Transcript describes this piece, as it arrived in Boston, “the original model,” which may perhaps have meant it was plaster.

The Boston Evening Transcript serves to chronicle Lander’s exhibitions in the 1860s and expands on the scale and history of her sculptures. The history of the Virginia Dare sculpture, as Lander noted in her pamphlet, was fraught with mishap: the sculpture was lost at sea, found, resurrected, and shipped on to America:

December 5, 1860. Miss Lander, the sculptor, is in town having lately returned from Rome, where she has executed some chefs d’oeuvre that have exacted the highest admiration abroad. We regret to learn that her marble life-sized statue of “Virginia Dare” expected shortly…has been lost at sea…Miss Lander’s last work, a large group, of “The White Mother Protecting Her Daughters from the Indians” is on its way to Boston…the group is three figures and stands six feet high…”

February 26, 1861. Miss Lander’s statue of Virginia Dare, lost at sea in the shipment from Leghorn, and washed ashore at Palos, Spain, and been recovered and reshipped to this country…Ship C.A. Stamler, with some of Miss Lander’s statuary on board put into St. Thomas…”

June 18, 1861. The barque Mary Annah, Capt. Grace, which arrived at this port on the 8th inst. From Leghorn, has on board five pieces of statuary by Miss Landor [sic]. One piece is large, and the subject is not given, but the whole will be on exhibition in this city in the fall. Her statuette of “Evangeline” will be exhibited at the stores of Mssrs. Williams & Everett in a few days (Williams and Everett Gallery).

June 24, 1861. The Statuette of Undine….at Williams & Everett’s…the water spirit rises as a jet from the unsealed fountain…clinging drapery and drooping form…ordered by a lady from Beacon Street. A reduced copy from Evangeline is also to be seen…

June 25, 1861. The original model of a group by the eminent sculptor, Miss Lander, was unpacked at the Athenaeum this afternoon. It represents American Defending her Children…will no doubt prove…to be one of the most popular of her numerous works…”

August 13, 1863. Miss Lander presented to the East India Maritime Society of Salem the original “The Pioneer Mother and Daughters” (see June 25, 1861).

Perspective

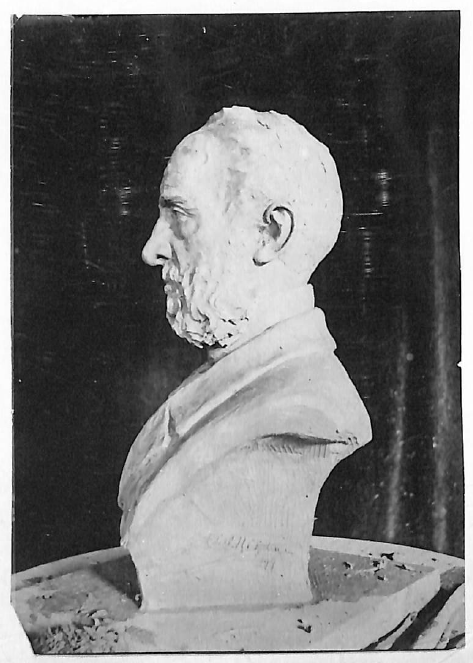

In 1890, Louisa Lander lived in Salem, Massachusetts and in the town census her occupation is listed as “sculptress.” It is not known if she produced sculpture in later life; or, if she did, whether it was ever reproduced in marble. In 1893, her sisters Elizabeth and Sarah having died, Louisa moved to Washington, DC, a few blocks from her brother Edward. A former federal judge, Edward lived near the Capitol building and was legal counsel for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Lander rented a home on 19th Street, near the White House. Lander’s portrait of him, in one existing photograph from the Stanford University Lander archives, is dated 185(?)9 and shows a bearded man in middle age resembling his known photographs. 37 It is clay, before being cast or carved, if indeed it ever was. After Edward died, Louisa returned to Massachusetts and lived on Beacon Street, Boston, for only a few months before she, too passed away in November, 1923.

No major works are recorded after about 1865. Perhaps the war derailed her, as did the deaths of Frederick and her father. Although she sold the life size Virginia Dare to a New York collector, he died before paying for the sculpture, and his heirs refused to honor the purchase. Louisa again took possession of her masterpiece. She tried to place it in the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, without success, and eventually willed the piece to the Historical Society of North Carolina. After further mishaps and being placed in storage, the sculpture is today a centerpiece of the Elizabethan Gardens on Roanoke Island. 38

In the very early twentieth century, when she was in her 80s, Louisa donated four small, possibly juvenile, works to the East India Marine Society (now the Peabody Essex Museum): three carved cameos and a small ceramic cup in the shape of a woman’s head, with butterflies forming a handle. 39 She had donated the lifesize “The Captive Pioneer Mother and Daughters” to the Society in 1863, and perhaps this last bequest of work was intended as a capstone to her career.

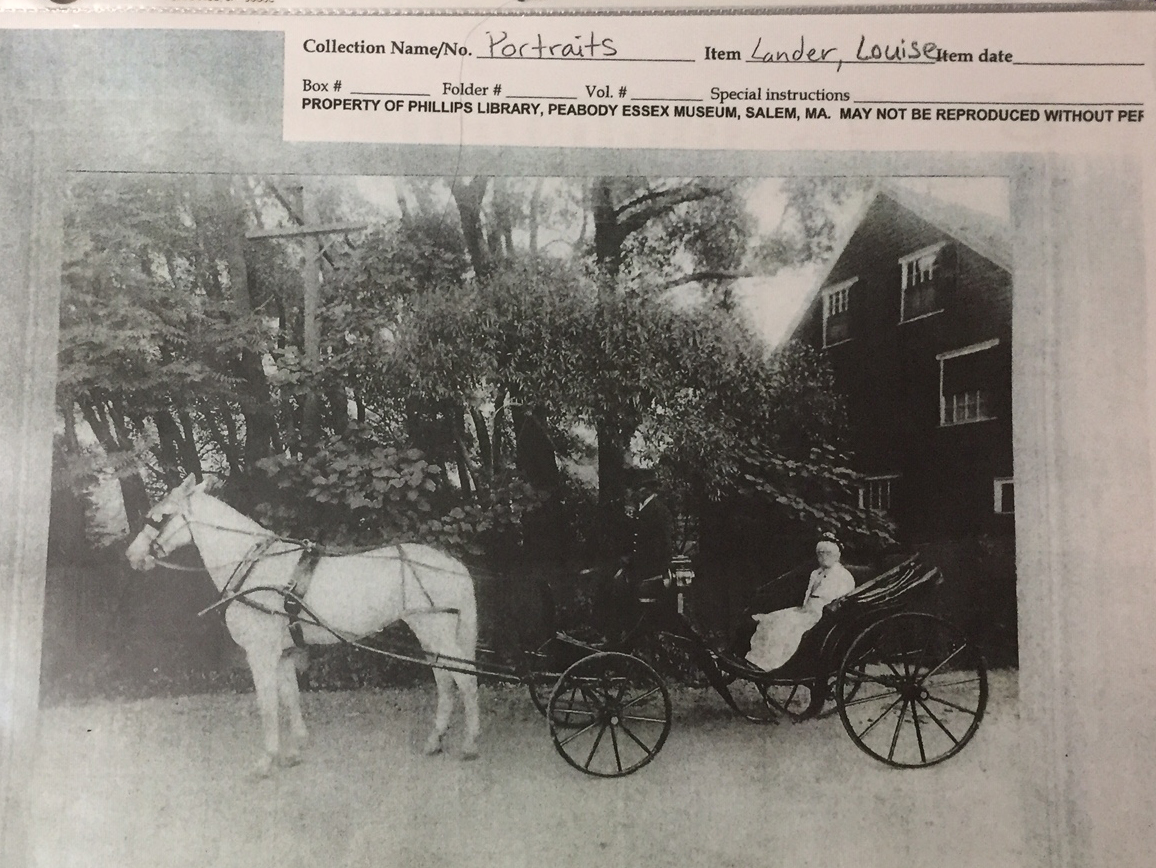

Lander inherited wealth in her later years, as her will demonstrates. An undated photograph, probably taken outside her large summer home on Beach Bluff Avenue in Swampscott, Massachusetts (called “Marblehead” by Lander), shows the artist as an alert, elderly dowager, seated in an immaculate Landaulet, or low-slung, open, one-horse carriage, driven by a man in top hat and livery. This conveyance, a quaint old thing in the 1920s, speaks to a vanishing upper-class mode of life; the carriage allows the occupant an unobstructed view of the sea as she is slowly driven along, but it also allows passers-by a good view of the occupant: well-dressed, well-to-do, and comfortable with being on display.40

Harriet Hosmer had also abandoned her sculpture career by the 1870s as commissions and interest in neoclassical sculpture drained away in favor of newer realism. Her creativity was unabated, however, and Hosmer remained busy designing inventions like a perpetual motion machine. She derided the new realism in art by calling new sculpture “bronze photographs.” 41

Louisa Lander outlived her art, her immediate family, and the position her social prominence once offered, but not, it seems, her many friends. She remained keen and insightful into old age, writing biographical notes on her brother Frederick, and choosing a summer home close to Salem and Lynn streetcar lines that would have allowed her to visit and receive visitors conveniently.

Sadly, we don’t have writings in Lander’s own voice, apart from an unsigned essay on Virginia Dare, and some short correspondence relating to her brother Frederick’s career. We can see little of her artwork. We have intriguing accounts written about her, and rave reviews. What we do know is that Lander created an oeuvre that celebrated women as independent, forthright protagonists. Aside from commissioned portraits, her chosen subjects were women from literature—including her own account of the Virginia Dare legend. She, almost alone in her era, conceived a radical pantheon of sculpted women whose poses, expressions, and symbolic attributes signified that they were independent people, not semi-erotic nudes designed for the male gaze.

Though slandered and gossiped about, there is something about Lander that refuses sentimentality. Her toughness, her refusal to answer to detractors in Rome, her willingness to “snap her fingers” at what she saw as unjust judgment, make her a more relevant personality to us than many of her contemporaries. Her singular vision was the result of a singular personality: strong willed, well-read, independent, highly intelligent: a talented professional pursuing a difficult craft among a circle of hostile peers.

Afterword

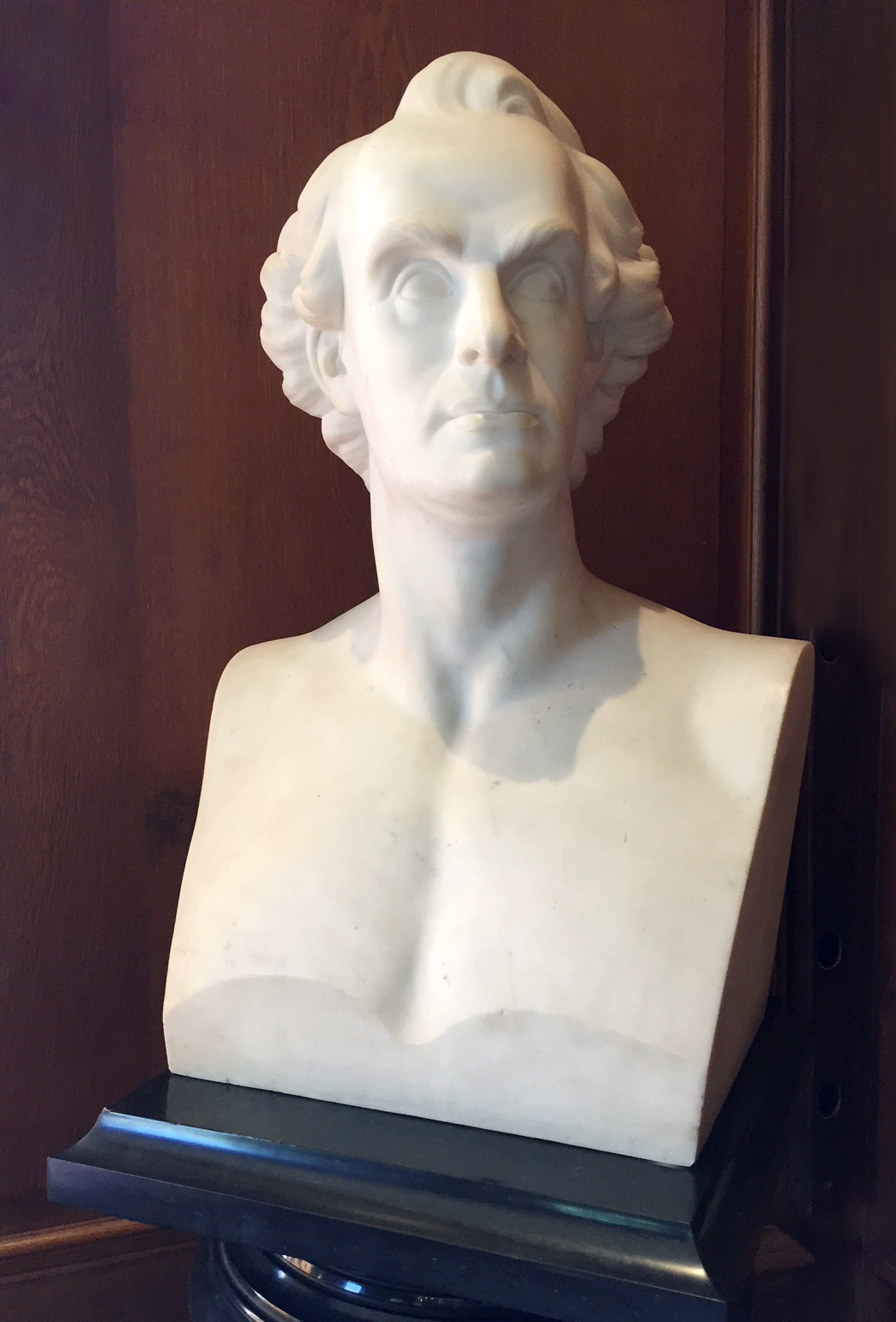

Few of Lander’s works are on public view: the Hawthorne bust is on the first floor of the Concord Free Public Library in Concord, Massachusetts. Virginia Dare is in the Elizabethan Gardens in Roanoke, North Carolina. One small cameo is in the Ropes Mansion in Salem, administered by the Peabody Essex Museum and open only in summer. The bust of Governor Gore is a private dining space in Memorial Hall, Harvard. As Lander may become better known, so perhaps her work will begin to emerge from storage rooms, attics, and all the forgotten spaces where it silently sits, unseen.

ADDENDA

Known Works (located works*)

Lander listed several completed works on the back page of the Virginia Dare pamphlet:

-To-Day (bust)

-Galatea (head)

-Maude Muller (bust, under life size)

-Evangeline (both 2/3 lifesize and 1/2 lifesize)

-Undine (sold to “Mary Warren on Beacon Street”)

-Virginia Dare (both statuette and life size)*

-Bust of Hawthorne*

-Bust of Governor Gore*

-Bust of Minister Pickens and Lady

-Portrait of Edward Lander (the artist’s father)

-A 6-foot group of 3 figures variously titled “The Pioneer Captive Mother and Daughter,” “Pioneer Mother Defending Her Children,” “America Defending Her Children,” “White Mother Defending Her Daughters”

In addition to Lander’s list, Elizabeth Ellet’s “letter from Rome” mentions several more pieces. Sometimes the scale is not given:

-Portrait of Judge Edward Lander. (Author’s note: A photograph exists in the Lander archives at Stanford University. The photograph is of a clay model, so it is not known if this was ever carved or cast. This portrait is Louisa’s brother Edward, the Federal Judge)*

-Elizabeth the Exile of Siberia

-A Sylph

-A bas-relief of Mountford

In A More Bracing Morning Atmosphere: Artistic Life in Salem, the author mentions a “religious piece for the Salem merchant John Bertram” although no specific subject matter is mentioned (p.161)

In the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum: A P.P. Caproni & Brother cast of the Hawthorne bust. A group of small (possible) juvenalia: three cameos and a small ceramic cup in the shape of a woman’s head.

Cosmopolitan Art Journal Vol. 5, No. 1 (March 1861), pp. 26-28 states: “In St. Petersburg she tarried long enough to do the bust of the American minister and his wife” (Pickens).

Authors Note: Under President James Buchanan, Francis Wilkinson Pickens was Minister (ambassador) to Russia from 1858–1860, He married his third wife, Lucy Petway Holcombe, in 1856 and she is likely in the double portrait.

_______________________

Lander’s Will

Beneficiaries Listed in Lander’s Will dated Dec. 3, 1923, filed in Washington DC:

Anna G. Endicott born about 1853, 22 Chestnut Street in Salem, held Lander’s funeral in November of 1923, bequest of “Telephone Stock” which would then pass to Louisa’s great-grand niece Margaret Lander Pierce.

Nieces and nephews in California: Sanger Pullman, George Pullman, Annette McDonald of Menlo Park, CA each $100

Grand nephews in Washington DC: Vinton Pierce of Washington (said “Chattels” including furniture), Josiah Pierce (Washington, furniture), and “all the residue of the estate” left her by her grandfather Nathaniel West. (presumably this is the remainder of the Oak Hill furniture)

Margaret Lander Pierce, child of Vinton (Lander’s great-great niece), received the statue of “Evangeline” now in a box in the front room, and some furniture, and $5,000

Mr. and Mrs. Charles E Kelsey (author’s note: b. about 1857 listed in 1902 census at 45 Beach Bluff Avenue Swampscott, occupation clerk), her Marblehead home and contents except for a picture and some furniture “for their kind care of me.”

9 women and 1 man as listed individually:

–Ada Stuart, Lafayette Louisiana $3,000

–Catherine Phelps, NY, $5,000

–Julia Brookhouse, Salem, $2,000

–Miss Emma Luscomb, Salem, $2,000

–Catherine Stone, Salem, $100

–Anna Fessenden, Salem, $100

–Mary D. Waters, Salem, $100

–Pickering George, Esquire, of Washington DC if he shall survive me, $500

–Dorothy Vaughan of Washington DC $200

–Mrs. William P. Annis formerly of Washington now Katonah NY $200

The Historical Society of Raleigh, NC—the statue of Virginia Dare

Will signed on July 1, 1922 as “Miss Louisa Lander”

Witnessed by: Ellen Maria Gannon, Barbara Thornton, Marie A. Seddicum

Lander and Siblings

–Elizabeth Rebecca Lander, b. about 1814 d. 4 Aug 1890 • Hale, Carroll, Missouri, United States

–Edward Lander born 11 Aug 1816 • Salem, Essex, Massachusetts, United States

Residence in 1880: 222 New Jersey Avenue Washington DC

d. 2 Feb 1907 • Washington, District of Columbia, United States

–Arthur Lander born abt 1818 • Salem, Essex, Massachusetts, United States (1818-?)

–Charles Henry West Lander (Feb. 1818-1877, died in San Francisco in 1877)

–Sarah West Lander (1819-1872) Born Nov. 27, 1819 Salem, MA

–Frederick William West Lander (General) 17 December 1821 – died of wounds 1862

–Maria Louisa Lander (1 Sept. 1826–November 14, 1923)

–Martha D Lander (1833-1873)

Lander’s Family and Places of Residence:

Born on Broad Street, Salem

Resided at Oak Hill (now Danvers), age 6 until her mother’s death in 1849 when LL was 23

After 1849: 5 Summer Street, Salem, the brick home built by her grandfather Nathaniel West

Summer Residence (built c. 1900): 45 Beach Bluff Road, Swampscott (called by LL Marblehead) MA

Washington, DC home: 1608 19th Street, a rented residence, two maids, listed in 1920 census

Last home: 821 Beacon Street, Boston (presumed demolished for Massachusetts Turnpike construction).

Death in Boston, MA November 1923 as Maria L. Lander age 98

Funeral at the home of Miss Anna Endicott, 22 Chestnut Street, Salem MA

Detailed Places of Residence (included are Lander’s father and siblings)

Listed in Salem City Directory: 1880, 1882, 1884, 1886, 1893

Listed in Washington, DC city directory: 1893, 1895, 1896, 1897, 1898, 1899, 1900, 1905, 1906, 1909, 1910

1850 Federal Census:

5 Summer Street in Salem, MA:

Edward Lander Age 60

Arthur Lander Age 32

Sarah Lander Age 26

Frederic Lander Age 24

Louisa Lander Age 22

Martha Lander Age 17

Bridget Mahoney age 35

1855 Federal Census:

5 Summer Street in Salem, MA:

Edward Lander Age 65

Arthur Lander Age 38

Sarah Lander Age 28

Louisa Lander Age 24 Birth year listed as 1831

Martha Lander Age 21

Mary Landers (sic) Age 25

Anna Green age 14

In 1862 Father Edward dies, leaving Louisa and her sisters the family property

1865 Federal Census:

5 Summer Street in Salem, MA:

Elizabeth R. Lander Age 50

Sarah Lander Age 45

Louisa Lander Age 36

Mary Harvey Age 28

1870 Federal Census:

5 Summer Street in Salem, MA:

Elizabeth R. Lander Age 50

Sarah W. Lander Age 49

Louisa Lander Age 42 Occupation listed as “sculptress”

1880 Federal Census:

5 Summer Street in Salem, MA:

Elizabeth R. Lander Age 65

Louisa Lander Age 51 Occupation listed as “sculpter” [sic] Birth year listed as 1829

*Note: death of sister Elizabeth in 1890, Sarah died in 1872

1920 Census

Residence in Washington, DC “Single head of household”

1608 19th Street, R (for Rented home)

Two Maids: Barbara Thornton and Annie Golden, both white and single

Full Text of Frederick Lander’s Virginia Dare Poem:

VIRGINIA DARE

She stands before us like a thing of dreams;

The glory of her thought is on her face;

And brokenly the tender sunlight streams

O’er the rapt wonder of her virgin grace:

Lo! the clasped hand; the faint and shadowy trace

Of bashful thought through all her woodland guise;

Pure, starborn dewdrop, that some floweret’s case

Holds up to heaven beneath the morning’s eyes,

That, trembling first, grows calm in softened, sweet surprise.

Hist! ‘twas the carol of some wakeful bird,

Or Nature’s voices wooing in the low

Sweet tone of flowers her loitering foot has stirred;

Or winds are wailing o’er the buds that glow

In chosen glades, and fear lest she go;

Or from the brook her Indian lover quaffed,

(More chill to him that Sewell’s mountain snow

since beauty passed) the rival zephyrs waft

O’er echoing waves his sighs that young Virginia laughed.

No, ‘tis the magic of a holier thought;

Fixed in new wonder by fond memories given,

Home, and the song her English mother taught,

Float with the sound, and lift those eyes to heaven;

So the fair Eve, on earth’s blessed day of seven,

Stood forth betwixt young Adam and the morn,

Ere mortal touch, or taint of earthly leaven,

Or that sad sense from evil knowledge born,

Had frayed the enraptured soul that thrilled her to adorn.

Ye arbiters of calling and true fame,

Translators of divinities ye blend

From faith and hope in Freedom’s household name;

Ye judges stern, whom sophistries offend,

Here view the grace that woman’s hand can lend

To all ye love; who, where eternal Rome

Bids artist souls to loftier themes ascend,

Could mould the tale of dear Virginia’s home,

And love her native land beneath a foreign dome.

Current Locations of Known Works:

In Peabody Essex Museum:

Three cameos and one white china cup in the shape of a head (all donated by LL in the early 20th century)

And

Plaster cast of Hawthorne bust (from PP Caproni & Bro. 1911 catalog) see personal email citation

Collection of Harvard University (Memorial Hall dining hall):

Bust of Governor Christopher Gore—life-size, marble

https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~memhall/sculptures.html

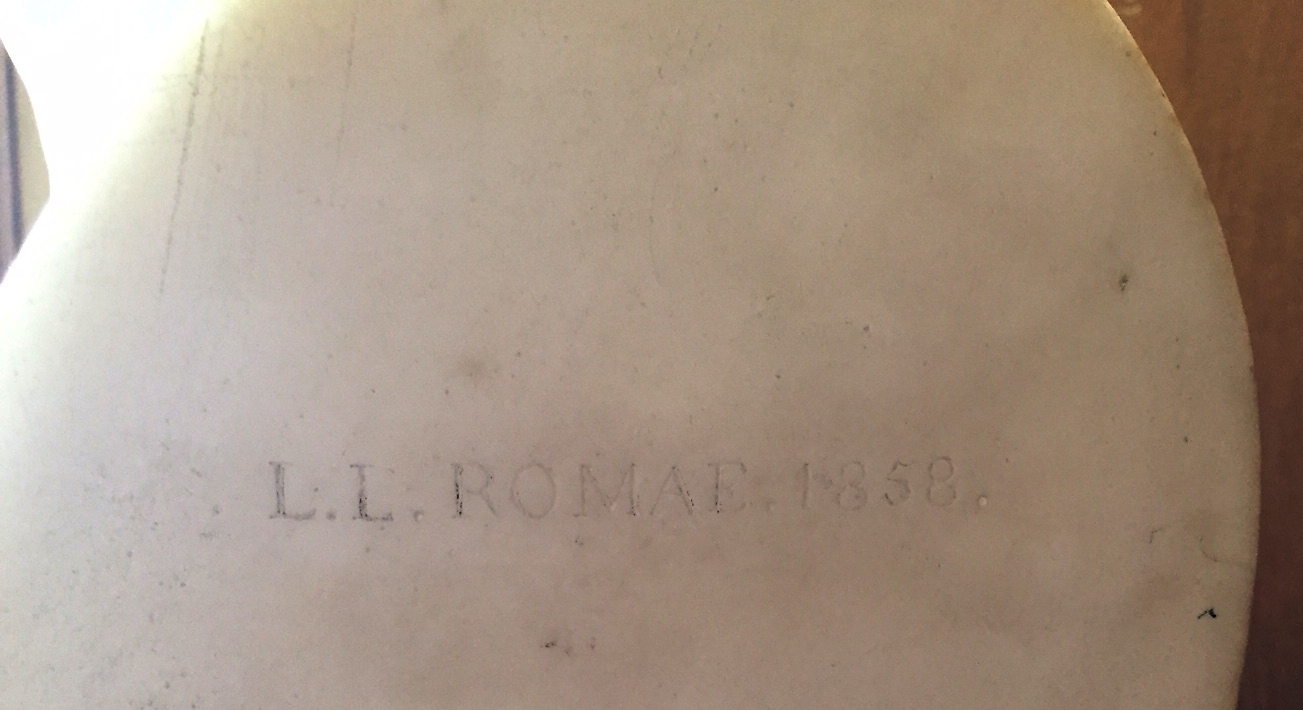

Collection of the Concord Free Public Library:

Marble bust of Hawthorne signed L.L. Romae 1858 (see author photographs)

Collection of PP Caproni & Brother (now owned by The Giust Gallery at Skylight Studios, Woburn, MA), Mold for plaster reproductions of the Hawthorne bust (presumably taken from the marble)

https://www.capronicollection.com/pages/historic-catalogs (1911)

Also see email message from The Giust Gallery to author, July 9 2018.

Elizabethan Gardens, Roanoke NC

Virginia Dare, lifesize, marble “Virginia Dare Statue in the Elizabethan Gardens” elizabethangardens.org

Citations

1 Thomas William Herringshaw, Herringshaw’s Encyclopedia of American Biography of the Nineteenth Century (Chicago, IL, USA: American Publishers Association, 1902), 568.

2 Doug Stewart, “Salem Sets Sail,” Smithsonian Magazine June 2004, accessed April 20, 2019

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/salem-sets-sail-2682502/

3 Elizabeth Fries Ellet, Women Artists in all Ages and Countries (New York : Harper & Brothers, 1859), 328.

4 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Oak Hill Rooms in American Period Rooms accessed April 22, 2019

https://www.mfa.org/collections/art-americas/tour/american-period-rooms

Musem of Fine Arts, Boston: Derby Chest on Chest by Samuel McIntire, accessed April 22, 2019

https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/chest-on-chest-38909

5 Dean Lahkinen, Samuel McIntire: Carving an American Style (Salem, Mass: Peabody Essex Museum, 2007), 244-245.

6 Cosmopolitan Art Journal Vol. 5, No. 1 (New York: March, 1861), 26-28.

7 Catalog of the Twenty-Eighth Exhibition of Paintings and Statuary at the Athenaeum Gallery 1855, (Boston: Eastburn’s Press, 1855), 15.

8 Ellet, Women Artists, 328-329.

9 Thayer Tolles, “American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad,” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000) Accessed April 22, 2019

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ambl/hd_ambl.htm

10 Ellet, Women Artists, 328-329.

11 Sylvia E. Crane, White Silence: Greenough, Powers, and Crawford, Sculptors in Nineteenth Century Italy (Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami Press, 1972) 365.

12 ibid.

13 New Perspective, New Discoveries: A New Look at Crawford’s Progress of Civilization, Architects of the Capitol, Capitol Restoration Project. Accessed April 22, 2019 https://www.aoc.gov/art/other-sculpture/progress-civilization-pediment

14 Giovanni Verri, Roman Sculpture and Color: The “Treu Head” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gRMPYh2QdSM&feature=youtu.be

Accessed April 22, 2019

15 “The Dusseldorf Gallery,” New York Times, March 13, 1860, 2.

16 John Idol, and Sterling Eisiminer, Hawthorne Sits for a Bust by Maria Louisa Lander, Essex Institute Historical Collections (vol. 114, October 1978): 207-212.

17 ibid.

18 ibid.

19 Ellet, Women Artists, 331-332.

20 Herbert, T. Walter, Dearest Beloved: The Hawthornes and the Making of the Middle-Class Family (Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford: The Regents of the University of California, University of California Press, 1993) 228-229.

21 Thomas Woodson, James A. Rubino, L. Neal Smith, and Norman Holmes Pearson, eds. Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Letters, 1857-1864, vol. 28. The Centenary Edition of the Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1987) 158-59.

22 Frederic A. Sharf, A More Bracing Morning Atmosphere: Artistic Life in Salem 1850-1859, Essex Institute Historical Collections (vol. 95, 1959): 149-164.

23 “Louisa Lander,” Salem Register June 24, 1858 np

24 Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, American Women Sculptors: A History of Women Working in Three Dimensions (New York : G K Hall, 1990) 59-60.

25 ibid.

26 ibid.

27 ibid., p. 41

28 ibid.

29 Cornelia Carr, ed. Harriet Hosmer: Letters and Memories (London: John Lane the Bodley Head 1913) 194-195.

30 Louisa Lander, The National Statue, Virginia Dare, Archives of The Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston: Box 1863. pamphlet, n.d. n.p. (4pp)

31 Frederick West Lander, “Virginia Dare” in Stanford University Archives Special Collections M102: Box 1, Folder 1, Item 3. Accessed digitally via personal email.

32 Boston Evening Transcript March 16, 1865, 2.

33 Cosmopolitan Art Journal Vol. 5, No. 1 (New York: March, 1861), 26-28.

34 Ellet, Women Artists, 331-332.

35 ibid.

36 Kathryn White, personal email from Peabody Essex Museum Collections Department, June 13, 2018

37 Stanford University Archives Special Collections: M102 Lander Family Papers, Box 1 Folder 3, item 28 photograph of Judge Lander. Accessed digitally via personal email.

38 Rubinstein, American Women Sculptors, 62.

39 Kathryn White, personal email from Peabody Essex Museum Collections Department, June 13, 2018.

40 Peabody Essex Museum Library and Archives at the Phillips Library, Rowley, Massachusetts: Fam. Mss. 540, Lander Family Papers, 1903-1904 .

41 Rubinstein, American Women Sculptors, 44.

List of Images and Images in Next Installment

Top to bottom:

Top to bottom:

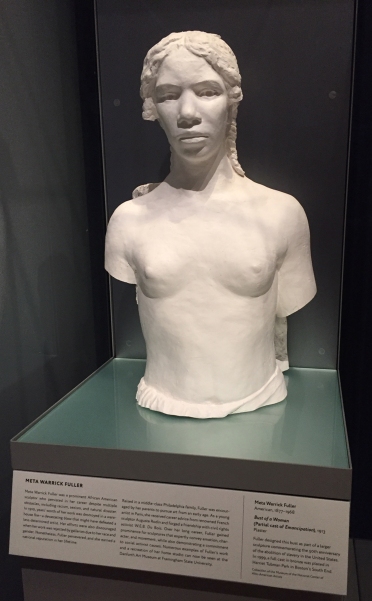

Margaret Cresson French

Margaret Cresson French